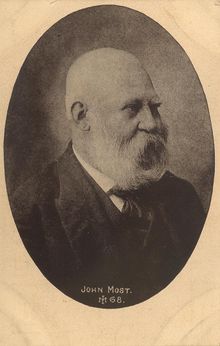

Johann Most

Johann Joseph "John" Most (1846 - 1906) was a German-American socialist — later anarchist — politician, newspaper editor, and orator. Most is best known for popularizing the anarchist strategy of "propaganda of the deed," which promoted direct action (including the use of violence) against individuals or institutions to inspire further action by others and to thereby generate revolutionary change.

Contents |

Biography

Early years

Johann Joseph Most was born February 5, 1846, in Augsburg, Bavaria to a mother who was employed as a governess and a father was a clerk. Neither of Most's parents had a fully sufficient income and City Hall denied them a marriage license, on the grounds that the applicants had failed to prove the required financial solvency.[1] His mother died of cholera while Most was still very young and he was soon subjected to the dictates of a proverbial cruel stepmother, a woman who made Johann carry water, build fires, wash clothes, clean lamps, and run errands before his meager morning meal.[1]

Most was also subjected to physical abuse at his stepmother's hand[1] and was further victimized by a sadistic schoolteacher (later committed to a mental institution) who made use of an array of whips and switches each time a student erred in arithmetic.[2] Religion was also part of his school curriculum and Most, an unbeliever from early days, was subjected to further beatings from teachers and priests for his insolence on religious matters.[3] To the end of his life Most was "a militant atheist with the zeal of a religious fanatic" who "knew more Scripture than many clergymen knew," his biographer notes.[4]

One night, sleeping in his unheated room, Most developed frostbite on the left side of his face. For several years thereafter, flesh rotted and infection spread, with the primitive medicine of the day unable to treat the condition.[1] His condition worsened and Most was diagnosed with terminal cancer.[1] As a last-gasp measure a surgeon was called in, who opened the left side of Most's face, removing infection, flesh, and bone before crudely stitching up the wound.[5] The grotesque physical effects of the surgeon's handiwork would mark Most's visage for the rest of his life.[2]

Most was apprenticed to a bookbinder, for whom he had to bind books from dawn until sunset, a condition which Most later likened to slavery.[6] At the age of 17 he became a journeyman bookbinder and plied his trade from town to town and job to job, working in 50 cities in 6 countries from 1863 to 1868.[7] In Vienna he was fired and placed on a blacklist for having staged a strike. Unemployable in his trade, he learned to make wooden boxes for hats, cigars, and matches, which he sold on the street until police brought an end to his trade for lacking a license.[8]

Political career

As the 1860s drew to a close, Most was won over to the ideas of international socialism, an emerging political movement in Germany and Austria. Most saw in the doctrines of Karl Marx and Ferdinand Lassalle a blueprint for a new egalitarian society and became a fervid supporter of the Social Democracy, as the Marxist movement was known in the day.[9]

Most engaged himself as editor of socialist newspapers in Chemnitz and Vienna, both suppressed by the authorities, and of the Berliner Freie Presse (Berlin Free Press). Most was a dedicated advocate of revolutionary socialism, sharing the views expressed by German socialist leader Wilhelm Liebknecht in an 1869 speech that "Socialism cannot be realized within the present state. Socialism must overturn the present state."[10]

In 1873, Most wrote and published a popular summary of Karl Marx's magnum opus, Das Kapital.[11] At Liebknecht's request, Marx and his associate Friedrich Engels themselves made some corrections to Most's text for a second edition published in 1876, despite the fact that the pair did not believe the pamphlet represented a satisfactory summary of Marx's economic work.[11]

In 1874, Most was elected as a Social Democratic deputy in the German Reichstag, in which he served until 1878.[12]

Most was repeatedly arrested for his violent and cynical attacks on patriotism and conventional religion and ethics, and for his gospel of terrorism, preached in prose and in many songs such as those in his Proletarier-Liederbuch (Proletarian Songbook). Some of his experiences in prison were recounted in the 1876 work, Die Bastille am Plotzensee: Blätter aus meinem Gefängniss-Tagebuch (The Bastille on the Plotzensee: Pages from my Prison Diary).

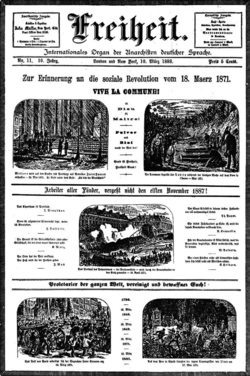

After advocating violent action, including the use of explosive bombs, as a mechanism to bring about revolutionary change, Most was forced into exile by the government. He went to France but was forced to leave at the end of 1878, settling in London. There he founded his own newspaper, Freiheit (Freedom), with the first issue coming off the press dated January 4, 1879.[13] Convinced by his own experience of the futility of parliamentary action, Most began to espouse the doctrine of anarchism, which lead to his expulsion from the German Social Democratic Party in 1880.[14]

In June 1881, Most expressed his delight in the pages of the Freiheit over the assassination of Alexander II of Russia and advocated its emulation; for this Most was imprisoned by British authorities for a year and a half.

Life in the United States

Encouraged by news of labor struggles and industrial disputes in the United States, Most emigrated himself to the USA upon his release from prison in 1882. He promptly began agitating in his adopted land among other German émigrés.

Most resumed the publication of the Freiheit in New York. He was imprisoned in 1886, again in 1887, and in 1902, the last time for two months for publishing after the assassination of President McKinley an editorial in which he argued that it was no crime to kill a ruler.

"Whoever looks at America will see: the ship is powered by stupidity, corruption, or prejudice," Most said.[15]

Most initially advocated a kind of collectivist anarchism.[16] While he later embraced anarchist communism,[17] Most's ideas are best viewed as part of the insurrectionary anarchist tradition.

Most was famous for stating the concept of the Propaganda of the Deed (Attentat): "The existing system will be quickest and most radically overthrown by the annihilation of its exponents. Therefore, massacres of the enemies of the people must be set in motion."[18] Most is best-known for a pamphlet published in 1885: The Science of Revolutionary Warfare, a how-to manual on the subject of bomb-making which earned the author the moniker "Dynamost."

A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman.

Inspired by Most's theories of Attentat, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, enraged by the deaths of workers during the Homestead strike, put words into action with Berkman's attempted assassination of Homestead factory manager Henry Clay Frick in 1892.

Berkman and Goldman were soon disillusioned by their mentor. Most became one of Berkman's most outspoken critics for the assassination attempt, despite, noted Goldman, having "proclaimed acts of violence from the housetops." Yet in Freiheit, Most attacked both Goldman and Berkman, implying Berkman's act was designed to arouse sympathy for Frick. Historian Alice Wexler suggests that Most's criticisms may have been inspired by jealousy of Berkman, although Wexler and others also credit Most's changing attitudes towards the effectiveness of political assassination in bringing about revolutionary change.[19]

Goldman was enraged by Most's critique, and demanded he prove his insinuations. When he refused to reply, she carried a horsewhip to his next lecture. After he refused to speak to her, she lashed him across the face, then broke the whip over her knee and threw the pieces at him.[20] She later regretted her assault, confiding to a friend, "At the age of twenty-three, one does not reason."

Death and legacy

Most continued to write and give speeches on the subject of revolutionary change for the remainder of his life. On March 17, 1906, while in Cincinnati, Ohio, to give a speech, he fell ill, and was diagnosed with a chronic case of erysipelas, a bacterial skin infection. In the era prior to antibiotic treatments, little could be done for his condition, which worsened, and he died a few days later, at the age of 60.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Frederic Trautmann, The Voice of Terror: A Biography of Johann Most. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980; pg. 4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pg. 5.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pg. 6.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pg. 7.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pp. 7-8.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pg. 8.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pg. 26.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Valeria Kunina and Velta Pospelova with Natalia Kalennikova (eds.), Karl Marx-Frederick Engels Collected Works: Volume 45: Marx and Engels, 1874-79. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1991; pg. 474, fn. 154.

- ↑ "Johann Most," Spartacus Schoolnet.

- ↑ Kunina and Pospelova with Kalennikova (eds.), Marx Engels Collected Works, vol. 45, pg. 508, footnote 466.

- ↑ Natalia Kalennikova, "Johann Joseph Most," in Marx Engels Collected Works, vol. 45, pg. 545.

- ↑ Most, Johann, "Anarchist Communism"

- ↑ Text of the 1883 Pittsburgh Proclamation

- ↑ Johann Most, "Anarchist Communism" (1889).

- ↑ Wendy McElroy, "Liberty on Violence".

- ↑ Alice Wexler, Emma Goldman: An Intimate Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984).

- ↑ Emma Goldman, Living My Life (1931)

Works

Note: This list includes only titles published in German or English. Some of Most's writings were translated into Italian, Spanish, Russian, Yiddish, French, Polish, and other languages.

- Neuestes Proletarier-Liederbuch von Verschiedenen Arbeiterdichtern (Latest Proletarian Songbook by Various Worker-Poets). Chemnitz: Druck und Verlag der Genossenschafts-Buchdruckerei, 1873.

- Kapital und Arbeit: Ein Populärer Auszug aus "Das Kapital" von Karl Marx (Capital and Labor: A Popular Excerpt from "Capital" by Karl Marx). Chemnitz: G. Rübner, n.d. [1873]. Revised 2nd edition, 1876.

- Die Pariser Commune vor den Berliner Gerichten: Eine Studie über Deutschpreussische Rechtszustände. (The Paris Commune in Front of Berlin Courts: A Study of German-Prussian Legal Conditions). Brunswick, Germany: Bracke Jr., 1875.

- Die Bastille am Plötzensee: Blätter aus meinem Gefängniss-Tagebuch (The Bastille on Plötzensee: Pages from my Prison Diary). Brunswick, Germany: W. Bracke, 1876.

- Der Kleinbürger und die Socialdemokratie: Ein Mahnwort an die Kleingewerbtreibenden (The Petty-Bourgeois and Social-Democracy: A Warning to Smal Businessmen). Augsburg: Verlag der Volksbuchhandlung, 1876.

- Gewerbe-Ordnung für das Deutsche Reich: Mit Erläuterung der für den Arbeiter wichtigsten Bestimmungen (The Industrial Code of the German Empire: With Commentary on the Most Important Provisions for the Worker). Leipzig: Verlag der Genossenschaftsbuchdruckerei, 1876.

- Freizügigkeits-Gesetz, Impf-Gesetz, Lohnbeschlagnahme-Gesetz, Haftpflicht-Gesetz: Mit Erläuterung der für den Arbeiter wichtigsten Bestimmungen (The Law on Freedom of Movement, the Law on Vaccination, the Law on Wage Attachment, the Law on Liability: With Commentary on the Most Important Provisions for the Worker). Leipzig: Verlag der Genossenschaftsbuchdruckerei, 1876.

- "Taktika" contra "Freiheit": Ein Wort zum Angriff und zur Abwehr ("Tactics" versus "Freedom": A Word on Attack and Defence). London: Freiheit, n.d. [c. 1881].

- Die Freie Gesellschaft: Eine Abhandlung über Principien und Taktik der Kommunistischen Anarchisten: Nebst Einem Polemischen Anhang (The Free Society: An Essay on the Plinciples and Tactics of teh Communist Anarchists: With a Polemical Appendix). New York: self-published, 1884.

- Revolutionäre Kriegswissenschaft: Eine Handbüchlein zur Anleitung Betreffend Gebrauches und Herstellung von Nitro-Glycerin, Dynamit, Schiessbaumwolle, Knallquecksilber, Bomben, Brandsätzen, Giften usw., usw. (The Science of Revolutionary Warfare: A Little Handbook of Instruction in the Use and Preparation of Nitroglycerine, Dynamite, Gun-Cotton, Fulminating Mercury, Bombs, Fuses, Poisons, Etc., Etc.). New York: Internationaler Zeitung-Verein, 1885.

- August Reinsdorf und die Propaganda der That. New York: self-published, 1885.

- Acht Jahre hinter Schloss und Riegel. Skizzen aus dem Leben Johann Most's. New York: self-published, 1886.

- An das Proletariat. New York: J. Müller, 1887.

- Die Hoelle von Blackwells Island. New York: self-published, 1887.

- Die Eigenthumsbestie. New York: J. Müller, 1887.

- Die Gottespest (The God Pestilence), New York: J. Müller, 1887. English: The Deistic Pestilence and Religious Plague of Man, n.d. [1880s]. Reissued as The God Pestilence.

- The Accusation! A Speech Delivered by John Most, at Kramer's Hall, New York, on November 13, 1887, in Denunciation of the Judicial Butchery of the Chicago Anarchists: For Delivering Which, He Has Been Sentenced to Twelve Month's Imprisonment by Judge Cowing. London: International Publishing Co., n.d. [c. 1887].

- Vive la Commune. New York: J. Müller, 1888.

- Der Stimmkasten. New York: J. Müller, 1888.

- The Beast of Property: Total Annihilation Proposed as the Only Infallible Remedy: The Curse of the World which Defeats the People's Emancipation. New Haven, CT: International Workingmen's Ass'n, Group New Haven, n.d. [c. 1890].

- The Social Monster: A Paper on Communism and Anarchism. New York: Bernhard and Schenck, 1890.

- The Free Society: Tract on Communism and Anarchy. New York: J. Müller, 1891.

- Zwischen Galgen und Zuchthaus. New York: J. Müller, 1892.

- Anarchy Defended by Anarchists. With Emma Goldman. New York: Blakely Hall, 1896.

- Down with the Anarchists! This is the War-Cry Raised by President Roosevelt and Echoed by the Congress of the United States. Now, Then, Hear the Other Side! The Anarchists will Take the Floor. Listen!. New York: John Most, n.d. [c. 1905].

- Memoiren, Erlebtes, Erforschtes und Erdachtes (Memoirs: Experiences, Explorations, and Thoughts). In 4 volumes. New York: Selbstverlag des Verfassers, 1903-1907.

Additional reading

- Frederic Trautmann, The Voice of Terror: A Biography of Johann Most. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980.

External links

- Johann Most Page Anarchist Encyclopedia

- Johann Most page at the Kate Sharpley Library